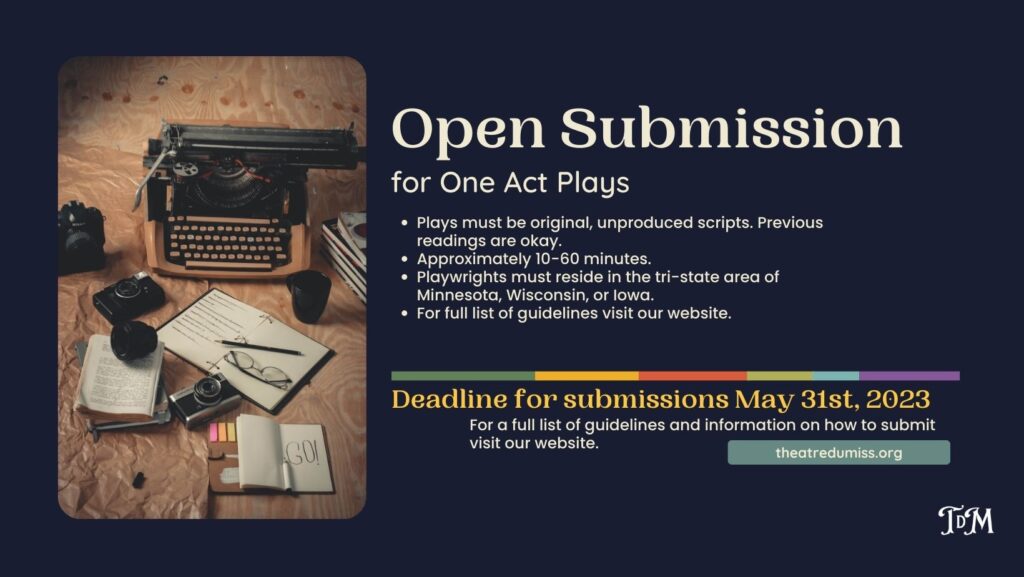

ONE ACT PLAY SUBMISSION GUIDELINES

1. Plays must be original, unproduced scripts. Previous readings are okay.

2. Scripts must be one-act, short plays, approximately 10 to 60 minutes in run time.

3. Playwrights must reside in the tri-state area of Minnesota, Wisconsin, or Iowa. We are looking to promote playwrights in our area in the region as described above. For purposes of this contest, a “resident” is anyone with a postal mailing address in the tri-state area.

4. Submissions must be “blind.” No name or identification attached to the script. Playwrights should clearly identify themselves and the name of the attached script in their cover letter email, and provide contact information.

5. Any genre, theme, or style of play is acceptable. We are not offended by foul language, but neither are we enamored by it. Use it wisely if you feel it’s necessary to your script. Ease of production will be considered in judging – if a complicated set design is necessary in the script, it would be less likely to be included. Similarly, the size of the cast will be considered. No more than six characters (or actors, if doubling is possible) is suggested. [Note: these are suggestions, not hard and fast rules. A great script is a great script.]

6. All scripts will be read and rated by a minimum of two readers, with positively rated scripts passed on to the judges. Judges will make final decisions after reading plays based on those readers’ reviews.

7. A list of judging criteria can be found on our website. We value those qualities that make for strong drama (i.e., action, conflict, dialog, imagery, etc.).

8. DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSIONS: all scripts must arrive in TdM’s inbox by 11:59 p.m. on May 31, 2023 or via New Play Exchange.

9. Winning scripts will be produced and performed as part of our One Act Play Festival dates and times TBD. Winning playwrights will receive a cash prize that will be determined at a later date. We intend to produce an approximately two-hour block of plays. The actual number of plays accepted (and thus, the amounts of the cash prize per playwright) will vary depending on the length of plays involved.

10. Scripts should be sent in either word or pdf format; for other formats, or hard copy submissions, please query to theatredumiss@gmail.com.

Please email us with your questions.

OUR JUDGING CRITERIA for reading one-act plays include the following elements:

ACTION: A plays begin in stasis. Stasis is interrupted by action. Action occurs when an event causes someone to do something. Or, to put it another way, action occurs when something happens that makes or permits something else to happen. Action is not necessarily physical; in fact, most action in a play is verbal. Character A tells Character B that his daughter has been taken to the hospital. B goes to the hospital, but Character C tells him he cannot see her. B then goes berserk and attacks C. Character D calls the police who, in turn, take B to jail. And so on. Action begets action and the play flows forward.

INTRUSION: Since the play begins in stasis, what will make it move? An intrusion of some sort. In “A Streetcar Named Desire”, Stanley and Stella’s world is in stasis. Then Blanche intrudes. Watch the dominos topple, until finally Blanche is taken away and their world returns to stasis. Changed, yes, but in stasis.

CONFLICT: The heart of drama is conflict. Dramatic conflict occurs when a character wants something and someone or something prevents him from getting it. Conflict is at the core of every good play. The greater the desire, and the more immovable the obstacle, the greater the conflict. Some impressive dramatic conflicts are those of Hamlet, King Lear, Oedipus, Romeo and Juliet.

THEATRICALITY: Good playwrights put their most important material in a theatrical moment. They do this to heighten audience attention. This can be lovers meeting for the first or last time, a death, a fight, change, or a devastating exit line. Remember Rhett Butler’s “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn”? Most of the titters and commentary was about the word “damn.” What many missed was how beautifully the statement summed up Rhett’s decision to terminate once and for all his obsession with Scarlett.

EXPOSITION: It should never be direct. Beware of past tense. It’s a sure sign of exposition. It stops the action. It breaks the tension. It loses the audience. A good playwright lets us figure out for ourselves what little we need to know about his characters through their actions and their dialog in real time. Be particularly aware of characters that tell each other what they already know for the benefit of the audience, which like Rhett Butler, doesn’t give a damn.

DIALOG: Low context dialog, e. g., idle chit-chat, exchange of pleasantries, mutual compliments, etc., is the mark of an inexperienced playwright. High context is derived from action.

Imagery in dialog plays an important role. The language must be carefully thought out. Words carry many different meanings than the expected. A careful playwright will choose language that lets the audience come to an understanding of the meaning intended, rather than telling him.

FORWARDS: This is an event or exchange of dialog that makes the audience hungry for what comes next. A good playwright uses them throughout his play. They are essential at the end of a scene and an act. Beckett does this superbly well in “Waiting for Godot”. When properly done, the audience is as eager for Godot’s arrival as Vladimir and Estragon.

CHARACTERS: A good playwright will give us the bones through the character’s actions, not his words. This allows the audience to provide the flesh. The character that tells you he is unhappy makes no mark. But let him show us his unhappiness and we see a real person. But never all of him. Characters in plays, like people in life, are always something of a mystery. Even to ourselves.

IMAGERY: The title should tell you something about the play by evoking an image. Williams, if you think about it, was a master at selecting titles. “A Glass Menagerie”, fragile and breakable; a family fragile and breakable. “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” a cat scrambling to get off; a family scrambling to get away from each other. “A Streetcar Named Desire”, a play of desire.

Good playwrights use repeating images. The moon in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” where the moon infuses all with a dream-like quality. The car in “How I Learned to Drive” and the latex glove in “Baltimore Waltz” about the brother dying of aids.